- Handbook of Robotics, 56th Edition, 2058 A.D."

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

The laws were first promulgated by science fiction writer Isaac Asimov in 1942 for his short story “Runaround”. In that story Robot SPD-13, “Speedy” becomes paralysed trying to resolve conflicts induced by trying to obey both the second and third laws.

In the spirit of binary computing Assimov later added an additional law. The Zeroth Law states, “A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm”. Following the structure of the other laws it is taken to be pre-eminent.

However, the addition of the zeroth law leads to unresolvable dilemmas as a robotic variant of the philosophical conundrum, “The trolley problem”.

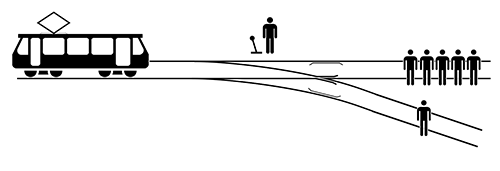

The initial description of the trolley problem is “The Switch”.

“There is a runaway trolley barreling down the railway tracks. Ahead, on the tracks, there are five people tied up and unable to move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, you notice that there is one person on the side track. You have two (and only two) options:

- Do nothing, in which case the trolley will kill the five people on the main track.

- Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track where it will kill one person.”

What do you do?

Most take a utilitarian approach; pull the lever. Yet minor tweaks to this scenario may flip your response.

Consider the alternative scenarios where:

- The person on the other track is your son.

- Instead of pulling a lever you push a fat man onto the tracks (whose mass will stop the trolley. (The fat man problem))

- The fat man is actually the villain who tied up the original five. (The fat villain problem)

The trolley problem has been studied by philosophers, psychologists, bioethicists and neuroscientists and has relevance in the fields of medicine, autonomous driving and the use of military drones to eliminate hostile forces.

The medical variant of the trolley problem states: “A brilliant transplant surgeon in a remote mountain village has five patients in dire need of a transplant: 2 kidneys, a liver, a heart-lung and a bone marrow. (We said he was brilliant.) A depressed but otherwise healthy young man without friends or family comes to this remote town and confides that he will soon end his life and will not be swayed.” What is the best action to take? Maximise outcomes or primum non nocere?

The covid pandemic and its management have raised many such ethical dilemmas. Travel restrictions, lockdowns, closure of schools and limits on social gatherings disrupted society and economic output plummeted. Social stability was maintained through government support that required it to go into hundreds of billions of dollars of debt. It is said that this will take several decades to reduce.

How much is a life worth? The question is unanswerable as the trolley problem demonstrates. Yet governments around the world have to make decisions that impact the health (and wealth) of current and future generations.

The question is unanswerable but that does not stop the market from having a go. Economists have derived the value of a statistical life (VSL) from surveys.

|

|

0 = Original Base Year; T = Updated Base Year; Pt = Price Index in Year t |

The US Environmental Protection Agency explains the concept by way of example.

“Suppose each person in a sample of 100,000 people were asked how much he or she would be willing to pay for a reduction in their individual risk of dying by 1 in 100,000, or 0.001%, over the next year. Since this reduction in risk would mean that we would expect one fewer death among the sample of 100,000 people over the next year on average, this is sometimes described as "one statistical life saved.” Now suppose that the average response to this hypothetical question was $100. Then the total dollar amount that the group would be willing to pay to save one statistical life in a year would be $100 per person × 100,000 people, or $10 million. This is what is meant by the "value of a statistical life.”

Using this approach the value of a life differs from country to country, depending on the income and the mores of the society. The table below gives some recent values.

|

Australia |

AU$5.1 million (2021) |

|

United States |

US$7.5 million (2020) |

|

New Zealand |

NZ$4.14 million (2016) |

|

India |

INR44.69 million (US $0.64 million - 2018) |

|

Turkey |

US$59,000 (2016) |

On this basis of these sorts of calculations it is said that saving a single American life is just as beneficial to society as saving the lives of 2 Saudis, 5 Romanians, 10 Macedonians, 35 Indians, 69 Haitians, 90 Sierra Leoneans, or 148 Liberians.

The US EPA however feels that expressing the data as a VSL is not helpful. They prefer the measurement, the Value of Mortality Risk (VMR), where the value is expressed in dollars per micro-risk per person per year. This is derived from exactly the same data as the VSL but does not sound so brutal and more accurately reflects the way the calculations are made.

In medicine the QALY (quality adjusted life year) is used to help guide treatment options. A person living for a year with optimal health gets a “one”. A dead person gets a “zero”. A medical “fate worse than death” is negative. Such calculations can be offered to patients with terminal disease and patients can make a choice about their discounted “net present value” in QALYs.

Such calculations can be fraught on both an individual and community level, however. The bioethicist's “rule of rescue” puts an onus on the physician to save an endangered life when possible. We will attend to the depression of our young man in the remote mountain village without giving thought to any other options.

Similarly health dollars are spent on high tech and expensive treatments that do little to prolong or improve a patient’s life expectancy whereas far less glamorous primary care and public health programs will result in much greater QALYs for the general community. General practice has long made these claims but it is hard to prove.

Spring sees Australia emerging from a severe winter of infections with influenza, RSV and other viral infections. Absences from work are now lower than in the years prior to covid. The third of our Covid-19 waves is abating with our infection rate in September a third of the previous month’s. We are two months behind the decline seen in western Europe and North America and the World Health Organisation has said that the end of the pandemic is in sight.

Former head of the Federal Department of Health, Jane Halton, is current chairman of the international Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations has said "If we don't see another particularly nasty variant I think people will be feeling quite optimistic," she has said. Halton is also reviewing Australia’s vaccine and COVID-19 treatment orders and her report is shortly to be delivered to the Minister for Health, Mark Butler.

There have been criticisms of Australia’s management of covid-19; the lockdowns were too long, the restrictions on gatherings and interstate travel too severe, not enough vaccines were ordered and were ordered too late.

Nevertheless, Australia followed the public health play book - restrict the spread of the infection and squash any outbreaks, then vaccinate the population and then manage the controlled spread of the disease throughout the community so that it does not overwhelm the hospital system. As a result Australia has had one of the lowest death rates from the covid-19 epidemic.

We pulled the switch and maximised the nation’s QALYs. Australia’s response to the pandemic was a success and our public health physicians are to be congratulated.