The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner

Grace Tame

Macmillan Australia 342pp

Book Review by Robin Osborne

One of the best-known names in Australia, Grace Tame has penned a memoir that is courageous, outspoken and predictably quirky. Noting from the outset that she has both autism and ADHD, the 27-year-year-old describes a life which, despite terrible tribulations, has been ‘on the whole… wonderful.’

Ms Tame is the second woman in recent years to become Australian of the Year (in 2021) for having spoken out against sexual or domestic abuse, the other being Rosie Batty (2015). Both have attracted abuse as well as widespread acclaim. She concedes that giving then-PM Scott Morrison the ‘stink eye’ did not win her friends in certain quarters.

Thanks to a photographic memory Ms Tame is able to detail a life that is so extraordinary it would make a wonderful book even without the dark events that inevitably lie at its core. She comes from a large extended family, lived for a time in Portugal, where she met a man whose past inspired the odd title, and then for years in east and west coast America. She is a passionate long-distance runner and has become a yoga teacher. She loves music and reels off lists of favourite bands.

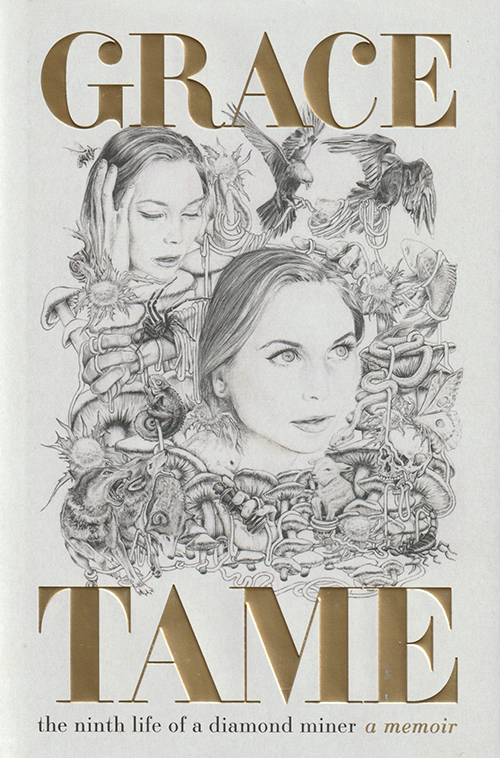

Grace Tame is also an accomplished graphic artist whose work illustrates the cover and is reproduced in colour plates. She created a pastiche of The Last Supper featuring characters from her beloved Monty Python and John Cleese’s Maine Coon cats. Cleese loved it, ordered hundreds of high-quality prints as merchandise for the Python’s US tour, and asked Ms Tame to join the company on the road. Naturally, she agreed.

Such stories are the backdrop to the grooming and serial assaulting in her early teens by a 58-year-old named Nicolaas Bester who was senior maths teacher at St Michael’s Collegiate in Hobart. A former South African soldier and a suspected child sex offender, Bester in 2011 tricked and coerced the young student into accompanying him to a secluded part of the school and painfully raped her. Many other encounters followed, both at the school and in outside locations, including a Hobart hotel.

Ms Tame provides uncomfortable details of these events as well as a considered analysis of the power relationships behind child sexual abuse.

‘Certainly, by far the most terrifying thing about my experience of child sexual abuse was not being aggressively penetrated on the floor by a man more than twice my size, who was older than my father, on the first day of maybe my fourth menstrual bleed ever,’ she writes.

‘Nor was it being told to undress in a closet after dark in a tiny storeroom in the dead of winter, and being struck by the gut punch of adrenaline because I thought we were just going to chat. It was listening, day in, day out, to the uncut thoughts of a psychopath who was convinced he would never get caught.’

Bester was outed after Ms Tame revealed the abuse to her parents, other adults and then the police, although the school offered him leave with full pay while investigations were being conducted.

The convicted abuser was out of jail with eighteen months and began studying for a PhD in chemistry while living in student accommodation on the University of Tasmania campus, a location which has ‘shared facilities including shower with teenage students.’ Ultimately, the UTas women’s collective pressured the administration into making Bester study remotely. Later, he would stalk Ms Tame online.

Understandably, revenge played a part in the book’s writing, yet in the main it is a dish served cold.

Ms Tame writes, ‘It is heavy, explicit, confronting and emotionally charged [yet] If nothing else, if this book is a blueprint for one person that helps them in some way, whatever that may be, my work here is done… Evil thrives in silence.’

She adds, ‘child abusers come in all shapes and sizes… However... child abuse is a crime against humanity… it is simply unforgivable. We must starve perpetrators of every possible excuse. Our main focus globally as a society should be on education and prevention rather than accepting child sexual abuse as a reality that we react and respond to.’