Around the globe, health professionals are on the front line of climate change impacts. This is because of the intimate relationship between the environment and human health. Climate change affects health and well-being through more frequent and severe weather events, as well as increased infectious disease risk, impacts of reduced food security and higher incidence of mental ill-health.

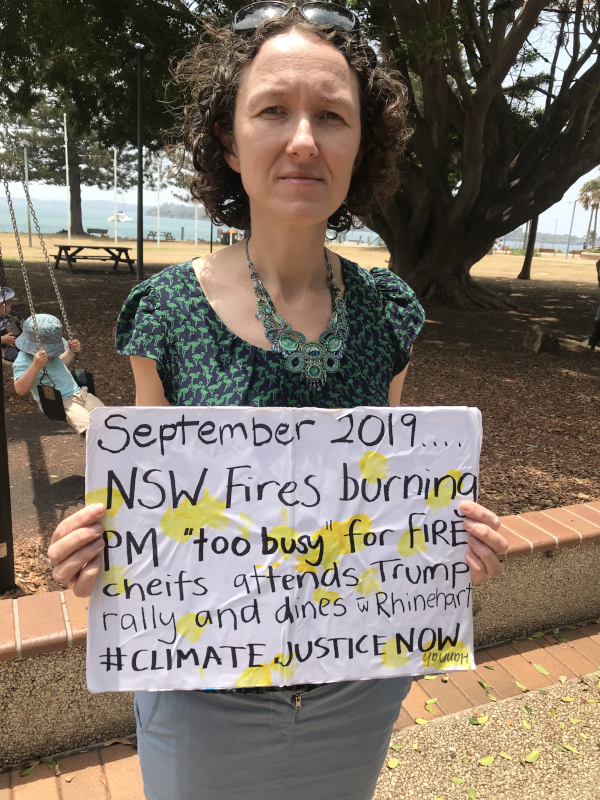

In the four years since the Australian Medical Association recognised climate change as a health emergency, citing severe impacts for patients and communities, we have experienced and witnessed these impacts at a regional level (flooding, bushfires), globally, and in some cases personally.

Doctors and other health professionals are frequently called upon as first responders during natural disasters and, in general practice, provide long term care during the recovery period following these events, as well as supporting patients with chronic health or mental health problems triggered or worsened by climate change impacts.

Increasingly there is also recognition of the carbon footprint of health care. In Australia health care is responsible for an estimated 7 per cent of Australia's CO2 equivalent (CO2e) emissions. Health care related CO2 emissions in Australia are driven by hospitals and pharmaceuticals, with hospital care being particularly emissions intensive.

As a complex problem involving multiple interrelated systems, responding to climate change successfully requires action by a critical mass of people at individual, community, industry, political and international levels.

Broadly speaking the response to climate change requires two types of action; mitigation, which focuses on drastically reducing the emission of CO2 and other greenhouse gases such as methane so that further heating is limited, and adaptation, which involves consideration of how to best prepare and respond to impacts from the heating which has already occurred.

This action can take place at individual, community or organisational, and state or national policy levels, and health professionals can contribute to both types of action at all levels.

Climate action at the individual level

Individual level action is an accessible entry point for many health professionals to contribute to climate action, often leading to co-benefits for the practice or patient.

At a home or business level, choosing energy efficient appliances, installing solar panels and switching to electric vehicles can lead to reductions in operational expenses alongside reduced CO2 emissions, due to the majority of the energy load for private practices occurring during daytime hours.

Reduced travel related CO2e emissions can also be achieved through appropriate use of telehealth, and through reducing carbon intensive travel, including air travel, for continuing professional development and other events.

Clinically, interventions oriented towards reducing unwarranted intensity or episodes of care (especially reducing preventable hospital admissions) are not only of benefit to patients but are also likely to contribute to reduced CO2e emissions. Other measures with significant co-benefits for patient health and climate change mitigation include lifestyle interventions that promote and support patients to use active transport, make dietary changes to increase the consumption of plant based foods and reduce exposure to air pollution through changing from gas to electric appliances.

In the general practice setting pharmaceutical prescribing is estimated to contribute between 65-90 per cent of CO2e emissions, and reviewing prescribing patterns, particularly for inhaled medications, can lead to significant reductions. The propellants used in some pressurised metered-dose inhaler (pMDI) devices are highly potent greenhouse gases, and switching to dry-powder inhalers (DPIs) or soft-mist inhalers (SMIs) where clinically appropriate can greatly reduce the carbon footprint of managing asthma and COPD.

Adaptation at an individual or professional level can include activities such as practice disaster planning, addressing needs of practice staff and patients during heat waves and periods of poor air quality and providing action plans for patients to use during heat waves, periods of poor air quality or natural disasters.

Climate action at community and organisational levels

Doctors and other health professionals are well positioned to work with stakeholders at a regional or community level and through inter-professional and inter-organisational relationships to advocate for and support climate change responses.

As respected voices in the community, doctors can make valuable contributions to local conversations about climate change and provide direct support to community-based education, mitigation and adaptation activities.

One recent local example of health professionals uniting to influence local conversations about climate change involved the submission of an open letter signed by 132 local health professionals to Port Macquarie Hastings Council (PMHC) as well as to local health organisations and members of parliament and political candidates that called for greater action on climate change at local, state and federal levels. The letter received local news coverage and contributed to efforts to encourage PMHC to declare a climate emergency (this was achieved in March 2021 before being rescinded by the council in February 2022).

Health professionals have also contributed to local community education activities in the Port Macquarie Hastings footprint through public events such as the Head Heart and Hands climate resilience project (2020-22), which ran webinars and face to face workshops on a range of health-related climate change adaptation topics including nature based mental health interventions, supporting children following disasters and nutrition.

In 2022 medical students at the rural clinical school in Port Macquarie ran a climate and health symposium providing climate change professional education for local students and clinicians.

In a professional role, doctors can advocate for and contribute to organisational efforts to decarbonise and adapt to climate change e.g. by driving or supporting local hospital energy efficiency and sustainability measures, participating in inter-organisational and multistakeholder disaster planning etc.

Climate action at a state, national or policy level

Health professionals can influence mitigation and adaptation efforts by politicians, government bodies and industry through a variety of mechanisms. When our position enables direct contributions to policy development this can be a particularly powerful mechanism, however doctors also hold considerable capacity for indirect contributions e.g by supporting and influencing the advocacy efforts of the RACGP, ACCRM and other colleges around climate change and through policy submissions and letter writing.

Organisations such as Doctors for the Environment Australia and the Climate and Health Alliance can provide support for health professionals wishing to engage at a political or policy level, and offer guidance around talking to members of parliament or the media about climate change, as well as the opportunity to work on submissions and policy papers.

Health Professionals can also contribute to political debate and the democratic process locally by supporting political candidates with demonstrated commitment to climate action, or by standing as a candidate.

Locally, registered nurse Carolyn Heise stood as an independent candidate for the seat of Cowper in the 2022 federal election resulting in a significant swing away from the Nationals based on a campaign platform that included stronger action for climate change.

Addressing barriers to climate action

Despite the scientific and moral imperative for climate action it can be difficult for many doctors to become involved. Anecdotally, time constraints, ethical concerns, imposter syndrome and a sense of overwhelm can act as barriers to action.

Time constraints are a constant challenge for the busy health professional, however at the individual level, many of the actions described above do not necessarily require us to do ‘more’ but to do things we are already doing, only differently.

Examples include recommending inhaled medications with a lower carbon footprint, choosing an electric vehicle when the company or family car is ready to be updated, or looking for local or online CPD activities rather than flying internationally.

Some health professionals may be concerned about the professional impact or ethics of sharing their views on climate change publicly, particularly given the longstanding media framing of the issue as a controversial debate. It may be reassuring to consider the high levels of community support for climate action, with the 2021 Climate of the Nation report finding that 75 per cent of Australians are concerned about climate change and high levels of support for actions to reduce carbon emissions.

Given the significant risks climate change poses to individual patients and public health, some authors have argued that there is a professional obligation for doctors and health professionals to address climate change both with individual patients and through health systems and advocacy – these issues were explored in depth in the December 2017 volume of the AMA Journal of Ethics.

A sense of imposter syndrome or concern about having insufficient knowledge to talk about climate change can make it difficult to speak up in a public forum. In advocacy work, talking from personal experience can be a powerful tool for communication and allow the health professional to feel more confident as they talk about an issue within their area of expertise – for example, sharing concerns about the impact of bushfire smoke on patients with asthma, or the mental health impacts they have observed following flooding.

There are now many resources available to health professionals to support the development of knowledge and skills required to advocate around climate change and health (see Box 1).

Like others concerned about climate change, doctors and other health professionals can experience eco-anxiety and a sense of being overwhelmed which can affect motivation and engagement. Health professionals are not only first responders to climate change impacts but often personally affected. The Australian Psychological Society highlights the benefits of taking environmentally responsible actions as a potent way to manage and reduce eco-anxiety, and has a range of resources to guide the development of adaptive coping strategies for climate change related distress.

Ready to Act?

Addressing climate change is an essential and urgent task, and health professionals can make a difference at individual, community or organisational, and state or national policy levels. Take a moment now to reflect on how you can contribute and explore the resources in the article to access the support you need to succeed.

Resources

Key resources to support climate action by doctors and other health professionals

- RACGP – Greening up: Environmental sustainability in general practice

- RACGP – Climate change and health – Practice posters

- RACGP – Managing emergencies in general practice

- Doctors for the Environment Australia – Fact Sheets [includes health professional education resources and patient handouts]

- Doctors for the Environment Australia – Membership

- Climate and Health Alliance – caha.org.au

- Australian Psychological Society – Climate change

- MJA – The 2022 report of the MJA-Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Australia unprepared and paying the price