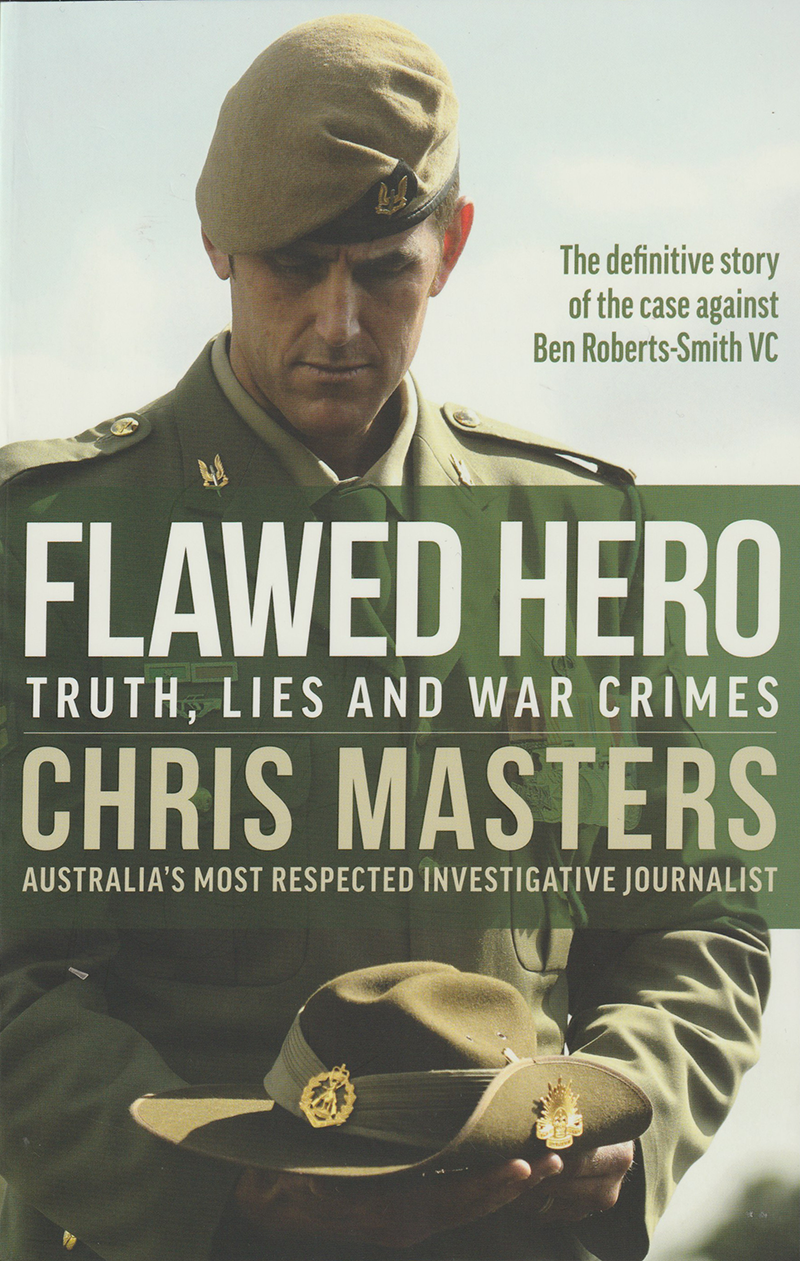

Flawed Hero Truth, Lies and War Crimes

by Chris Masters, Allen &Unwin 566pp

Not long into this hefty account it becomes clear that the title is remarkably generous. Ben Roberts-Smith VC, MG was not so much a “flawed hero”, although he was certainly that, but, in the words of one of his comrades in arms, ‘an infant who ends up believing his own fantasies’, ‘a showboating piece of shit’, ‘a big boofhead’.

In more poetic words, Chris Masters, whose work includes books based on officially-approved embedding with the military in Afghanistan, calls him a “counterfeit exemplar” whose elevation to hero status did nobody, including the man himself, any favours.

Many of the other Special Air Service Regiment (SASR) personnel who served with or, often to their regret, under Roberts-Smith were similarly disparaging, not least those who were bullied by the 2.02 m (6’6”) “Big Ben”, or worse, punched by him for alleged operational shortcomings.

As unlikeable as he appears, there is no doubt that BRS, as he is known, was a good soldier, ‘good’ in the sense of battling, and most often killing, what he called the “bad cunts” who inhabited the Taliban infested parts of Afghanistan where Australian troops were deployed. BRS won the Victoria Cross for bravery, later questioned, for his engagement in a battle in 2010.

More controversial were the allegations that BRS, who had never risen above the rank of corporal, was involved in the execution of captive Afghans, including the civilians killed at a compound bearing the military identifier of “Whiskey 108”. Here, according to a number of SASR witnesses (and Afghans who were later interviewed) but denied by others, BRS kicked a man named Ali Jan over a cliff and then directed that he be shot.

The prosthetic leg of another executed detainee was taken back to the SASR base where it would be used as a drinking vessel in the bar (officers not welcomed) known as the Fat Lady’s Arms.

These abuses during Australia’s “longest war” were reported in the Fairfax (later, NINE Media) press and 60 Minutes, as well as The Canberra Times, all within the bounds of our defamation laws, by Chris Masters, the author of this book, and Nick McKenzie, who has authored his own account, Crossing the Line. The word “lies” features in the titles of both, and the court transcripts feature a host of them, told by those loyal to, or in fear of, BRS.

The truth tellers, equal in number, were mostly former troopers, even though many were subpoenaed to appear. To be seen as ratting on mates was the ultimate breach of the regiment’s code of silence, whatever the merits. Receiving praise is Capt. Andrew Hastie, now a federal MP, who, fuelled by strong Christian beliefs, was no BRS fan.

Along with other identified excesses, a.k.a. alleged war crimes, these events would also be referred to the Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force whose 2020 report found “credible information of war crimes committed by the ADF in Afghanistan between 2005 and 2016”.

The nub of the story is the defamation action taken against the journalists by BRS and his admirer Kerry Stokes, the WA media magnate and former chair of the Australian War Memorial, an institution that had lionised Roberts-Smith’s military achievements. (See previous article in NorDocs.)

The action swings between two disparate battlefields, southern Afghanistan, where the Australians were fighting the “bad cunts” who would eventually take over the country, and the Sydney courtroom where the Stokes-funded lawyers would seek to show that the journalists had pursued an unprovable vendetta against the country’s most decorated modern warrior.

Their high-priced battalion included Bruce McClintock SC and Arthur Moses SC, who late in the trial would hit the news as the lover of disgraced former NSW Premier Gladys Berejikilan.

The journalists’ team included revered silk Sandy Dawson, who would be stricken by a brain tumour before the trial ended, the unflappable Nicholas Owens SC, and some gun (pardon the pun) legal researchers.

As we now know, the defamation claim failed, leaving BRS with a sullied reputation and massive legal fees that were still being disputed at the time of writing. An appeal is also being pursued, with even more costs likely.

BRS could have chosen to live quietly as, in the words of the title, a flawed hero – assuming he was not prosecuted for war crimes – albeit minus the wife and other women he had cheated on, and in one case, allegedly assaulted.

Instead, fuelled by hubris, he chose to storm the enemy’s position, with the ensuing legal process revealing much that might have remained hidden.

This is a complex and important book, peppered with court transcripts, details of the Afghan theatre, and a mass of military abbreviations and acronyms, one of the commonest being “PUC”, a person under control, many of whom ended up dead.

Not surprisingly, the better known “PTSD” often figures, with SASR operatives apparently having a high level of psychological distress post-discharge.

Why did BRS act as he did? According to the author, ‘essentially because his mentor, Kerry Stokes, had the funds to back him.

‘The war hero cum Seven executive probably felt he had no choice. The allegations against him were too serious to ignore. Yes, it would have been more sensible to keep his powder dry for any criminal trial, but back in 2018 [the trial ran for 110 days and Justice Anthony Besanko’s ruling for 700 pages], when the statement of claim was filed, he had cause to believe he would win.’

One wonders if BRS’s father, a retired judge, didn’t advise him otherwise. Perhaps he had blind faith in his son, as did far too many Australians. In all likelihood, Australia’s longest war still has a long tail.