We all know the Achilles tendon. Most of us will also know the tendon is named after the ancient Greek mythological figure Achilles because it lies at the only part of his body that was still vulnerable after his mother had dipped him (holding him by the heel) into the River Styx.

Even for mere mortals the tendon remains a vulnerable part of our body, especially as we get older, and its chronic conditions can be difficult to treat. Understanding each particular condition can make our job easier and allow us to give informed advice to our patients, ensuring they recover faster and avoid unnecessary treatment and expense.

Chronic conditions of the Achilles can be broken up broadly into “insertional” and “non-insertional” problems based on the location of pathology.

- Insertional problems make up around 25% of these and include three distinct entities:

- Insertional Achilles tendonopathy (IAT)

- Retrocalcaneal bursitis (RB)

- Subcutaneous bursitis (SB).

- Non-insertional Achilles tendonopathy (NIT) accounts for around 65% of chronic conditions. The remaining 10% can be attributed to chronic rupture.

Anatomically, three muscles contribute to the Achilles tendon and they cross up to three joints. Soleus crosses the ankle and subtalar joints, whereas gastrocnemius and plantaris cross the knee as well. Plantaris is a small vestigial muscle which contributes little to function but can play a part in Achilles tendon pathology.

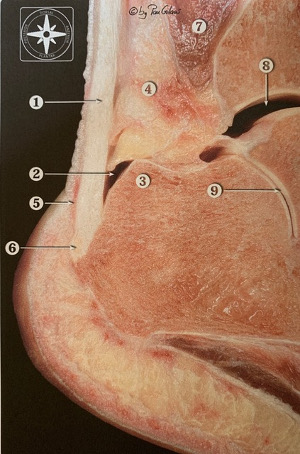

Figure 1. Cross section of the Achilles Tendon Insertion. 1: Achilles tendon, 2: Retrocalcaneal bursa, 3: Posterosuperior process of calcaneus, 4: Kager’s fat pad, 5: Subcutaneous bursa, 6: Achilles tendon insertion, 7: Flexor hallicus longus muscle.

The Achilles (Figure 1) inserts into the inferior half of the posterior surface of the calcaneus. Between the tendon and the superior half of this surface lies the retrocalcaneal bursa. A prominent posterosuperior process may contribute to the development of bursitis as the Achilles wraps around it with dorsiflexion. The retrotendonous or superficial bursa, when present, is an acquired structure.

The Achilles itself is composed of collagen fibril bundles surrounded by a peritendineum (endotenon, epitenon and paratenon) over the top of which is the deep fascia.

Diagnosis can be made in most cases with history and examination but x-ray provides additional useful information. Ultrasound adds nothing.

Factors predisposing to pathology vary according to the specific condition. Age, obesity, new or unaccustomed activity, abnormal limb biomechanics (such as a cavovarus foot), inflammatory arthropathy or gout may contribute to insertional Achilles tendonopathyor retrocalcaneal bursitis.

Subcutaneous bursitis, known to Americans as the “pump bump” is classically caused by friction from the hard heel counter of a pump style shoe.

Non-insertional Achilles tendonopathy has been described as a condition associated with long distance running but in 30% of cases patients are sedentary. Half of the population at age 66 show changes of tendonosis however the majority are asymptomatic.

Clinically, patients will complain of pain, worse with activity. As the condition progresses pain can be present at rest and at night especially with IAT and NIT. RB may be worse immediately on walking after rest. Discomfort in shoes can be common to all but especially SB. Some patients may be able to accurately localise the pain.

These conditions may of course co-exist so I find the single most useful part of the examination is location of tenderness:

- IAT: central at insertion

- RB: medial and lateral to Achilles at insertion

- SB: posterolateral insertion

- NIT: 2-6 cm proximal to insertion (often but not always associated with a swelling of the Achilles).

The diagnosis can be made in most cases with history and examination but x-ray provides additional useful information. Ultrasound adds nothing. I generally reserve MRI for those considering surgery AND where the primary pathology remains unclear.

Insertional conditions display distinctive findings on x-ray. A typical posterior heel spur will be seen with IAT.

Fig 2. Kager’s fat pad sign. Upper diagram and x-ray : normal.

Lower diagram and x-ray: retrocalcaneal bursitis with loss of definition of the soft tissue angle and a prominent posterosuperior process.

The findings of RB are more subtle but look for a prominent posterosuperior calcaneal process and Kager’s Fat Pad Sign (Figure 2). Kager’s fat pad is seen as a black soft tissue triangle on a lateral x-ray bounded by the Achilles tendon posteriorly, the flexor hallicus longus muscle anteriorly and the calcaneus inferiorly. Normally, the angle where the Achilles meets the calcaneus is a sharp, acute, well defined angle. This angle becomes indistinct and blurred with RB due to scarring, swelling, and debris in the bursa.

An x-ray of SB is generally normal. Although NIT will display no distinct findings itself, an x-ray may display co-existing pathology.

Seventy percent of patients will respond to non-operative treatment. IAT and NIT are not inflammatory processes histologically so NSAIDS provide an analgesic role only. Any form of injection should be avoided, particularly steroids due the risk of rupture. I find simple heel lifts from the chemist can be helpful and are a cheap alternative to orthotics. The only two forms of non-operative treatment with strong evidence to support their use are eccentric strengthening exercises and shock wave therapy (similar to that used to treat kidney stones). A physiotherapist or an appropriate podiatrist is a good place to start.

Failing a minimum of three months non-operative treatment, surgery can be considered. The procedure depends on the condition but with better understanding of each and improved techniques the outcomes are very encouraging.

IAT still requires an open operation but with advances in suture anchor technology it is now quite safe to detach the entire Achilles tendon from the bone enabling complete debridement of diseased soft tissue and bone. The tendon is then reattached and mobilisation is commenced at two weeks.

RB can be treated endoscopically as day surgery and the patient starts walking again in two weeks.

There is growing evidence that the pain of NIT comes not from the tendon itself (only 65% of symptomatic tendons are abnormal on US and cadaver studies) but from the peritendineum which in chronic cases displays neurovascular proliferation and myofibroblast induced scarring. With this knowledge, surgical treatment in the majority of NIT cases can be confined to keyhole “tendoscopic” stripping of the deep fascia and paratenon from the tendon, denervating the Achilles, freeing it from adhesions and releasing plantaris.

So yes, the largest tendon in the body is vulnerable, but it need not be your Achilles heel.