Healthy North Coast (HNC) is looking to update its Board advisory structure.

HNC welcomed four new Board members this year following the Annual General Meeting in December 2020. The newly elected members are Graeme Innes and Kerry Stubbs (as previously reported in Nordocs magazine, Autumn 2021). The newly appointed members are Sam Hardjono and Rebecca Bell who came highly recommended from the HNC Nominations Committee.

Sam has wide ranging experience in various sectors, including international, inter-governmental, not-for-profit and corporate spheres, as well as in private companies and start-ups. He is a director of the Australian Red Cross and holds a MBA in international business.

Rebecca trained as an occupational therapist and for the last 12 years has worked in local and national community and health organisations. She currently works at the corporate level in Medibank Private and is also a director of the Sunshine Coast PHN and CASPA Family Services.

Since the establishment of Australia’s Primary Health Networks in 2015 there has been no change to the advisory structures to the Board. Initially there were four clinical councils that met on a bi-monthly basis. They represented their local geographic areas of Tweed, Richmond, Coffs Harbour and Port Macquarie and were based on four of the founding organisations of HNC, the original Divisions of General Practice.

Over time the Divisions have mostly folded or become disillusioned with the PHN experiment. Mid North Coast, based in Coffs Harbour, is the only member of the original Divisions actively involved in the clinical network. Clinical advice to the Board from its existing Clinical Advisory Committees has waned over the last several years.

The current Board advisory structure now comprises just three clinical councils based on the North Coast, Mid North Coast and Hastings-Macleay. The total number of health professionals on the three councils is limited to 60. Meetings are held bi-monthly.

The committees are diverse, representing all primary health care workers in the area although currently nearly 50 percent of the members are general practitioners and under current guidelines this level is considered too high.

One of the goals of the revised structure is to get health practitioners to actively engage with NCPHN through the Clinical Councils. A key to achieving this will be to give the Councils some degree of ownership in improving the health system. General practitioners felt their contributions were valued under the Divisions of General Practice and Medicare Locals but this feeling has diminished under the revised PHN scheme. The challenge for the PHNs is to recapture that commitment and to extend it to the other primary health care professionals.

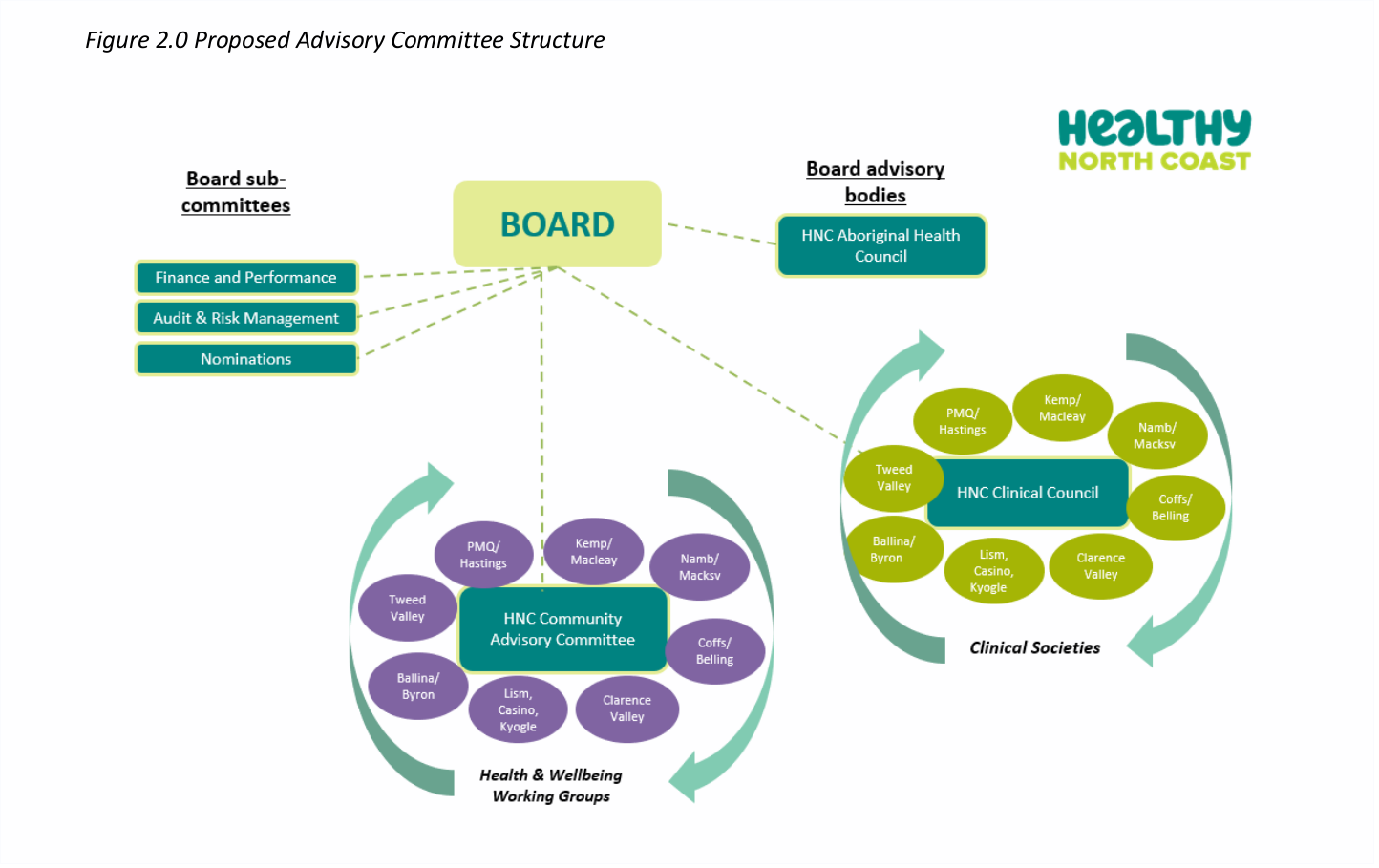

One proposed scenario is that the current three Clinical Councils are combined into one that would cover the whole PHN footprint. The number of members will be reduced from 60 to 20. The remuneration for participating on the Council will be increased from its current level of $135 per meeting to reflect the increased commitment and responsibilities of Council members.

To ensure that the Council’s voice is heard and is relevant to the secondary health system both the Board and the Local Health Districts will have representation on the Council.

The most contentious aspect of the new proposal is that local health practitioners can bring their concerns and issues to the PHN via the newly formed Clinical Societies. There are now eight societies across the NCPHN with local meetings every second month. The mechanics of providing feedback have not been determined at this stage and will no doubt require input from clinicians themselves.

Under the Department of Health’s guidelines the local PHNs also need to canvas community views on their programs and direction. The new proposal for NCPHN recommends establishing eight Community Councils aligned along the same geographic boundaries as the new Clinical Councils.

Active community involvement in health and education has long been considered best practice in community development. However, it is always a difficult task to get meaningful engagement from the general public where individual representatives often have quite restricted or parochial interests. Few members of the general public have the breadth of knowledge across the whole domain to take a leadership role. Once again the PHN will face significant challenges in creating and maintaining active participation.

HNC’s recent review also identifies under-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within the organisation as a major issue. To address this the HNC is considering a separate stand-alone Aboriginal Health Council that would report directly to the Board. This is a worthwhile approach to trial, but as with the Clinical Council, their voice will need to be heard at Board level and having ATSI representation on the Board will be a prerequisite to ensuring this.

The new advisory structure is a step forward. It gives Clinical Council members a much more powerful voice in the organisation that can now be heard at Board level. It also opens the door for more meaningful integration with the hospital sector where there is abundant room for better cooperation and coordination. It is hoped that the new structure is just the first step in once again bridging the primary/secondary sector divide.

We commend HNC on this step forward and trust that the Clinical Council members are heard and their views respected. Failure to do so would again compromise meaningful engagement.