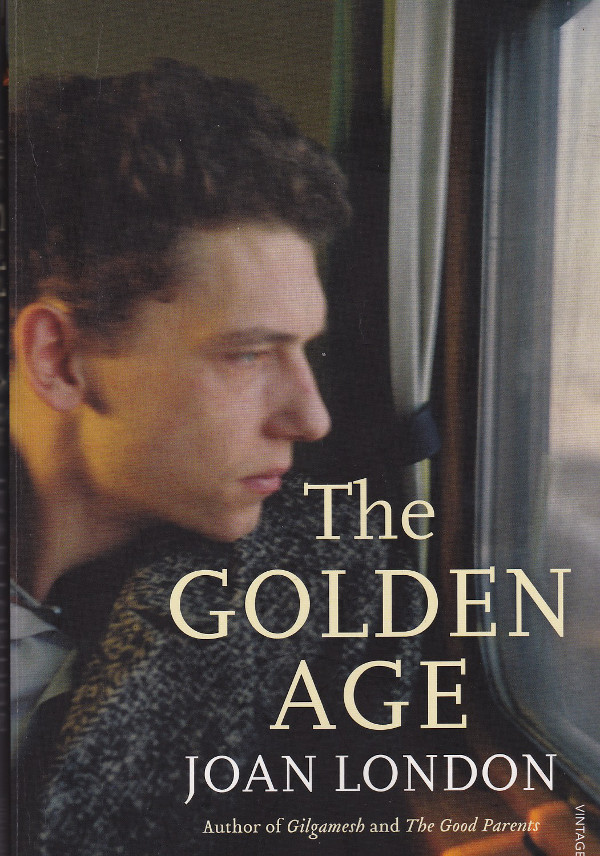

The Golden Age by Joan London (Vintage Books $32.99)

Barely a memory these days, especially by the younger generation that was most susceptible to it, the scourge of polio lies at the core of Joan London’s third novel, set in a children’s convalescent home in Perth that, with cruel irony, bears the name of the book’s title.

In fact it was once a pub, as the author informs us, built in the late 19th century and later converted by the health department into a home “to service the years of the great epidemics.”

Oddly, the name closely resembles that of the central character, 13-year-old Frank Gold, the son of wartime refugees from Hungary who has contracted polio and been transferred here because it was deemed unsuitable to be amongst adult patients at the Infectious Diseases Branch of the Royal Perth Hospital.

The year is 1954, and vaccine for polio is yet to be developed. As a result, many children’s lives hang in the balance, the prospect of being crippled for life considered a good outcome.

Despite the upbeat nursing staff, portrayed sympathetically, the facility is bleak, especially for those undergoing that most ghastly of management regimes, respiration in an ‘iron lung’. It is here that Frank meets another patient, Sullivan Backhouse, who will change his life.

“He pushed through the heavy doors into a ward where four large portholed tanks were lined up like submarines in dock. The room was filled with the sound of their ghostly, rhythmic breathing… Coffins you lived in. The worst thing that polio could do to you, next to death.”

Despite the physical barrier, the pair form a close friendship, with Backhouse’s fondness for poetry, including the advice that it doesn’t need to rhyme, inspiring the younger, more mobile boy.

“Poetry didn’t have to be about heroics, Sullivan said. It didn’t have to strut about. It could sound like someone speaking. It could be about personal things. Big things were happening now in poetry, new movements in the United States… Once you get used to your condition, he said, your imagination becomes free again.”

Despite his superior education and well-placed family, Backhouse is not long for this world, but the spark he generates in his ‘New Australian’ friend lives on, and soon Frank is composing his own poetry, jotting down verses that mostly don’t rhyme on a leftover prescription pad.

Soon his eye is caught and his heart captured by another patient, Elsa, an attractive lass whose reliance on calipers invariably prompts onlookers to regard her as ‘poor Elsa’, bound to be denied a proper life by the debilitating disease. Not so, as it transpires.

The juvenile romance progresses to an indiscreet if immature physicality that results in both being expelled from the Golden Age and returned in disgrace to their families. While things take an upturn, and they are briefly reunited, their lives diverge in later life, Frank becoming a writer, childless, living in New York, and Elsa a doctor and mother, in Australia.

Like London’s previous works, this is a beautifully penned story, marked by uncomplex yet most satisfying writing, and peopled by characters finely observed, not least Frank’s immigrant parents, so disillusioned by 1950s Australia, and the health impact they feel it has had on their beloved son. The freedom they have found does not deliver happiness. That is the reward for the next generation, despite his childhood travails.