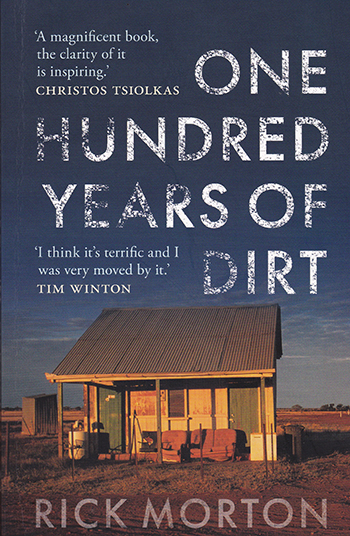

One Hundred Years of Dirt

Rick Morton

Melbourne University Press - 191pp

Although relatively short this memoir by Rick Morton comes across as a number of books in one, mostly very moving and something of a wake-up call for those who would discriminate against rural dwellers, people of differing sexualities and those with mental health conditions.

The author, who rose from dirt poor Queensland roots to become a senior journalist with The Australian, fits all three categories and harbours understandable anger for many of his life experiences.

If one ‘book’ sits uneasily in this mix it is his temptation to deliver a broadside at inner-city ‘latte sippers’, notably certain politicians and their supporters in the media. Which is to say media organisations not part of the Murdoch stable.

“…this brand of politics prioritises the woe of people who can afford to worry about anything other than paying the bills and feeding themselves.”

For which read climate change, asylum seekers et al.

Now one of the paper’s senior editors, Morton might best have take the red pen to such thoughts, leaving us with a tale that goes some way towards justifying the cover quotes from Christos Tsiolkas (“A magnificent book…”) and Tim Winton (“I think it’s terrific and I was very moved by it”).

Hailing from a family that had once owned “0.4 per cent of the entire Australian landmass”, a property near the Queensland-SA border, he would be raised in poverty by a loving mother, fond memories of whom run through the book, and an abusive father who would eventually take off with his lover.

Then his own problems began emerging, becoming more profound in his teens with the rising awareness that he was gay in an era and a place that judged such a ‘transgression’ harshly.

“I’ve never had my brain scanned,” Morton writes, “though I wonder how much my impulsive and short-sighted life skills l owe to the stress of those years from age six.”

These adverse childhood experiences and his struggle with sexuality would translate into alcohol and drug abuse, and an inability to form close relationships or manage his money: “The cruel twist of poverty is that a person with no money pays more for everything… you could never buy in bulk, nor take advantage of early payment rewards, Interest rates tend to be higher, especially for emergency loans…”

Things were not helped by the chaotic lifestyle of his drug dependent brother, who had been dreadfully burned in a childhood accident, and soon enough Morton’s own mental health issues.

Ever the journalistic researcher, he focuses on Australia’s confused battle with substance misuse, sexual biases and mental health, this being a major strength of the book.

“”Gay people have their stress response triggered so often and almost without pause during their youth that the mechanism just stops working efficiently,” he writes.

“The stress comes not from being called a faggot every day or avoiding a hate crime. That might happen; it has happened to all of us many times. The point is that it could happen on any day and our mid-evolution brains activate the fight-or-flight response in advance.”

Alarmingly, as he notes, “Suicide becomes an option somewhere along the way, when all other options cease to become viable. Or at least that’s how I sold it to myself as my body broke into my mind.”

Accessing higher education and achieving his long-held dream of becoming a journalist, at first in regional press and now with a national daily, Morton has succeeded in a way that other family members have not. Now he has written a valuable insight into how sizable numbers of people, especially those abused or neglected as children, find the odds stacked against them.