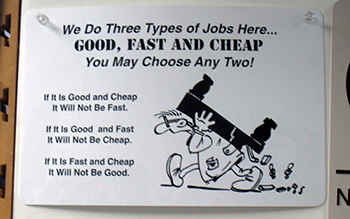

“Good, fast, cheap. Pick any two.”

This business aphorism reflecting the economics of scarcity is relevant to most aspects of human behaviour. If something is good, demand rises quickly and suppliers are then faced with three choices; increase the price, delay the delivery time for the goods or services, or reduce quality.

One can escape from these economic constraints only through developing new techniques or innovations that allow for faster, better or cheaper delivery without compromising any of the other parameters, at least to any great extent.

Doctors have a fair idea of what constitutes good medical practice. GPs have encapsulated these principles in the basic tenets of the “Medical Home”. In Australia the Medical Home is a person-centred offering, comprehensive, continuous and coordinated care that is readily accessible and of high standard.

For patients the question is much more difficult. They have no domain specific knowledge of their problem. They, largely, cannot tell good quality from bad, at least initially. However, they readily understand time and money and may base their decisions on those parameters.

As can also be the case with lawyers and accountants, helping a customer get through a major life event or crisis will cement most professional relationships. The professional is in there for the long haul and looks after the patient’s/client’s interests. Their value comes to the fore on those occasions when the stakes are high.

Medicine differs from most other disciplines in that the government is a third party to the transaction. Like patients themselves the government cannot readily assess the quality of the care provided. However, unlike patients, that does not change much over time. The focus for the government thus becomes buying the greatest number of services at the cheapest price.

As the sole insurer of medical services at the primary care and specialist level the government has extensive monopsony power over the medical profession. It uses this to counter the extensive power the profession has in determining its own prices.

Medicare rebates have never kept pace with inflation and have been frozen for seven of the last eight years. The fixed price has resulted in more frequent but shorter consultations over time. It is argued by most medical practitioners - and patients would hardly disagree - that shorter consultations are of lesser value.

In Australia co-payments are permissible. Patients can make an out of pocket payment for a medical service from a particular practitioner for what they deem to be a “better product”.

Providing a “better product” is also good for the provider. Practitioners derive more satisfaction from their work when they can afford to provide a higher quality of care and are incentivised to explore ways of doing things better.

The relationship between control over your environment and happiness was established many years ago. In the eighties Australian trained epidemiologist Michael Marmot examined the relationship between increased work stress and poorer health, and control over the work environment in the British civil service; the higher up in the pecking order and the more control you have over your workflow, the better your health and well being.

In other countries co-payments are not permitted. Doctors in these systems have less control over their working arrangements and are frequently demoralised by the system. Primary care practitioners in those countries are far less happy with their lot than Australian GPs.

Each year the Australian Productivity Commission reports on the health system. The 2019 report was released in late January 2020 and found that Australian general practice was largely fulfilling the criteria of the “medical home” with more than 90% of patients agreeing that the GP listened closely, showed respect and spent enough time with them.

Over 95% could afford the GP visit and medications and 80% got an appointment within an acceptable time frame.

The Commission’s report largely confines itself to data and statistics, preferring inferences to be drawn by others. It did note, perhaps wryly, that dentists outperformed GPs on all criteria except... timeliness and affordability!

The continuing squeeze on GPs’ incomes has made general practice a less attractive specialty. The failure of the GP training program to fill its quota last year, combined with the high percentage of GPs approaching retirement age, suggests a skill and workforce shortage is likely in the coming years. Given the trends for an ageing population and high burden of chronic disease such a development could be catastrophic.

The AMA and RACGP have long argued for increased remuneration for general practice and the point is once again made in the AMA’s submission for the 2020-2021 budget. With their past record of success - i.e. the lack thereof - in influencing government financial decisions GPs should not be too hopeful of meaningful increases in the near future.

With the mounting pressures on the entire health system it remains to be seen if the current trends towards using behavioural economics and specialty services will successfully replace general practice for an ageing population.